The market for “free TikTok likes” has grown into a small but persistent corner of the online attention economy, sitting at the intersection of creator income, social commerce and digital advertising measurement. What looks like a harmless shortcut for boosting a post can create problems that quickly become financial: distorted campaign reporting for brands, higher fraud losses for platforms and payment providers, and regulatory exposure for businesses that rely on inflated popularity signals to sell goods or attract sponsors.

Pressure is rising because the money around TikTok has expanded beyond ads. TikTok Shop has pushed deeper into everyday retail, and creators increasingly use livestreams and short videos to sell products, drive affiliate commissions and collect tips through virtual gifts. As that ecosystem grows, so does the value of a visible metric like “likes” and “views” and the incentive for third parties to manipulate it.

Regulators have also started treating fake engagement less as internet noise and more as a consumer protection issue. In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission has moved against practices tied to deceptive reviews and influence indicators, including the sale of fake followers and views, a shift that broadens risk for brands and marketing intermediaries that knowingly participate in the market for synthetic popularity, according to Reuters reporting.

The underlying business logic is simple. Platforms and advertisers use engagement signals to decide what to recommend, what to sponsor, and sometimes what to stock and discount. If those signals are manipulated, money can be misallocated. Brands may pay for campaigns that do not reach real customers. Sellers may overestimate demand. Creators may build strategies around metrics that collapse when the artificial boost disappears. And consumers can be steered toward products and accounts that look more trusted than they truly are.

The attention economy meets payments

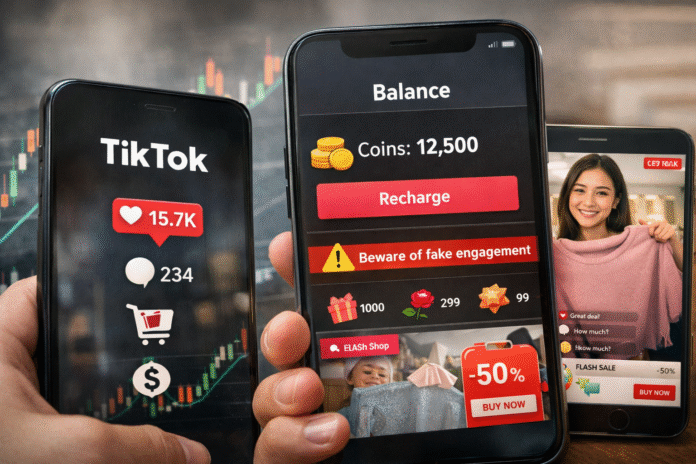

For TikTok itself and for creators, engagement is increasingly connected to payments. Users can buy TikTok coins inside the app and use them to send Gifts during LIVE streams. TikTok’s help materials describe Coins as purchasable packages through the Balance menu and note age requirements for purchasing. These Gifts can translate into “Diamonds” for creators, which TikTok describes as a virtual item used to recognise creator popularity and contributions, with rewards eligibility tied to Diamonds collected.

This is where engagement manipulation becomes more than vanity. Livestream gifting, promotions, and shopping are all influenced by visibility. If a creator’s content is boosted by fake engagement, it could attract real users who then spend real money on Coins, or buy products featured in videos. That creates a risk of consumer deception — not necessarily because any one “like” is a promise, but because the overall presentation of popularity can influence buying decisions.

The same dynamic applies to TikTok Shop marketing. TikTok’s seller education materials explain how sellers can create promotions such as a TikTok Shop promo code, with parameters like code format and a validity window, and discount rate constraints. Those tools are legitimate, but they also encourage an environment where sellers compete for attention inside a single feed. In a crowded marketplace, the temptation to “juice” engagement can rise, especially for new shops trying to rank.

None of this means social commerce is inherently untrustworthy. It does mean the incentives are sharp. When likes and views become a form of currency that affects distribution, advertising pricing and retail conversion, the market for “free” metrics tends to attract fraud.

Why “free” engagement often isn’t free

The phrase “free TikTok likes” typically signals one of three models: manipulation through bots, “engagement exchange” schemes that trade activity between accounts, or phishing and credential collection dressed up as growth services. The details vary, but the financial risk is consistent.

First, synthetic engagement can impair campaign reporting. If a brand pays for creator marketing and the engagement is partially artificial, the brand’s return on ad spend may look better than it is, which can lead to repeated spending on ineffective channels. Over time, that mismeasurement becomes a budgeting problem.

Second, it can create account security and payment risk. Growth schemes that ask for logins, verification codes, or other access can lead to account takeover. If a compromised account has payment methods attached for in-app purchases, the losses can move beyond social metrics and into direct financial theft. Public reporting has documented cases where TikTok’s gifting economy was involved in misuse of funds, underlining how quickly virtual goods can translate into real-world costs.

Third, it can create compliance exposure. In the US, regulators have made clear that fake indicators of influence can be treated as deceptive in a commercial context, which matters for influencers, agencies and brands that profit from endorsements. In the UK, enforcement focus has also intensified around online manipulation and transparency. The Competition and Markets Authority has published guidance on fake reviews and concealed incentivised reviews under updated consumer law frameworks.

This matters because the lines between “review,” “endorsement,” and “social proof” blur on short-form video. A product can be promoted without a formal star rating, yet still rely on apparent popularity to persuade buyers. Regulators are increasingly interested in whether consumers are being misled by undisclosed incentives or manipulated signals, even when the content looks like entertainment rather than advertising.

US, UK and EU: a tightening perimeter around manipulation

Regulatory approaches differ, but the direction is similar: greater scrutiny of deception, especially when it affects purchasing decisions.

In the US, the FTC’s rulemaking and enforcement posture has signalled that selling or using fake popularity signals in monetised contexts can be treated as unlawful. For marketers, the key issue is knowledge and intent: whether a party knowingly buys, sells, or benefits from deceptive indicators. The practical implication is that some tactics that once lived in a grey zone are moving closer to clearly regulated conduct when tied to commerce.

In the UK, the CMA has stepped up its work on fake reviews and endorsements, publishing detailed guidance that describes what counts as fake or concealed incentivised reviews and how consumer law applies. The UK’s advertising watchdog has also focused on disclosure and transparency in influencer marketing, publishing guidance and reporting on ad disclosure rates on platforms including TikTok. While disclosure is not the same issue as fake likes, both sit under the wider umbrella of consumer transparency: what is real, what is paid, and what is being made to look more popular than it is.

In the EU, the Digital Services Act framework increases expectations for large platforms to assess and mitigate systemic risks and to provide transparency around how online ecosystems function. The DSA is broader than engagement fraud, but its focus on risk management and accountability adds pressure on platforms to show that they are not ignoring manipulation that could harm users.

For global brands, these differences can become a cross-border operational issue. A campaign may be planned in one market, executed globally, and measured using the same engagement metrics everywhere. If some of those metrics are manipulated, the risk does not stay neatly within one jurisdiction.

What users actually see: Stories, shopping and the trust gap

Some of the most searched TikTok phrases point to a wider trust gap: people want to know what is visible, what is private, and what is real.

Take the TikTok story viewer question. TikTok’s help pages explain that Stories can show who viewed them, and that viewers may be visible to the Story creator. That transparency can be useful, but it also creates demand for third-party “viewer” tools that claim to offer anonymous viewing. Those tools can introduce privacy and security risks, and they often sit adjacent to the same ecosystem that sells “free likes” and other artificial boosts.

The same trust issue shows up in shopping. Promo codes and platform discounts are legitimate, and TikTok provides formal tools for sellers to create promo codes with structured limits. But users also encounter unofficial coupon pages and third-party promotions of unclear origin. When shoppers are deciding whether a deal is real, visible engagement can become part of the decision: a highly liked product video can look like validation, even if the engagement was not earned organically.

This is one reason social commerce has become a finance story, not just a tech story. Payments, incentives, and behavioural nudges are embedded inside entertainment feeds, and the boundary between “content performance” and “commercial performance” is thin.

Readers tracking TikTok’s broader policy and ownership uncertainty in the United States may also see the engagement issue as part of a larger risk narrative: regulators are asking more questions about platform governance, transparency, and the downstream impacts of algorithmic distribution. For background on the US policy debate, see Blinkfeed’s coverage of the TikTok deal.

Table

The commercial risk becomes clearer when you map common TikTok monetisation tools to the incentives they create. The table below is descriptive, not predictive, and the “what to watch” column reflects areas regulators and platforms have publicly emphasised.

| TikTok feature or market | What it is | Why it matters financially | What to watch next |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Free TikTok likes” offers | Third-party attempts to inflate engagement | Can distort ad pricing, mislead brands, and increase fraud losses | Enforcement against deceptive practices and platform removals of artificial engagement |

| TikTok Coins and Gifts | In-app purchases used to send virtual gifts during LIVE | Converts attention into paid digital goods; raises payment and fraud stakes | Platform policy updates and consumer complaints tied to virtual goods |

| Diamonds (creator rewards signal) | Virtual item TikTok uses to recognise creators based on popularity/contribution | Links popularity to reward eligibility; encourages competition for visibility | Continued scrutiny of monetisation incentives and transparency |

| TikTok Shop promo code tools | Seller-created discounts managed in Seller Center | Discounts drive conversion; competition may raise incentive to manipulate social proof | Greater focus on authenticity of endorsements and shopping claims |

| TikTok Stories viewer visibility | Stories can show who viewed them | Creates privacy demand and a market for risky third-party tools | Platform privacy settings changes and scams tied to “viewer” tools |

What to watch for in 2026: measurement, enforcement, and platform strategy

There are three developments worth watching as the market around TikTok evolves.

First is measurement. Brands and agencies are under pressure to prove outcomes, not just reach. As budgets tighten in parts of the advertising market, advertisers may rely more heavily on conversion data and less on surface metrics like likes. That shift could reduce the value of fake engagement over time, but it also pushes fraud into more complex areas such as fake clicks and synthetic purchases.

Second is enforcement. The US and UK moves against deceptive practices, combined with EU platform accountability rules, create a more hostile environment for obvious manipulation. Even when enforcement is uneven, the existence of clear rules can change corporate behaviour, because large brands do not want reputational risk from being linked to fake influence markets.

Third is platform strategy. TikTok’s commercial ambitions rely on user trust: shoppers need confidence in offers, creators need predictable monetisation rules, and advertisers need reliable measurement. The platform’s own help pages emphasise formal systems for Coins, Gifts, and Shop promotions, which suggests a desire to keep commerce inside controlled channels. The more money flows through those channels, the more incentive TikTok has to limit third-party manipulation that undermines trust.

The “free TikTok likes” market is unlikely to vanish entirely. But the broader direction towards more regulated, payment-linked, commerce-heavy social platforms makes the downside bigger than it was in the early era of influencer culture. In finance terms, that means higher fraud risk, higher compliance costs, and higher scrutiny on how digital attention is priced.

Table

| TikTok feature or market | What it is | Why it matters financially | What to watch next |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Free TikTok likes” offers | Third-party attempts to inflate engagement | Can distort ad pricing, mislead brands, and increase fraud losses | Enforcement against deceptive practices and platform removals of artificial engagement |

| TikTok Coins and Gifts | In-app purchases used to send virtual gifts during LIVE | Converts attention into paid digital goods; raises payment and fraud stakes | Platform policy updates and consumer complaints tied to virtual goods |

| Diamonds (creator rewards signal) | Virtual item TikTok uses to recognise creators based on popularity/contribution | Links popularity to reward eligibility; encourages competition for visibility | Continued scrutiny of monetisation incentives and transparency |

| TikTok Shop promo code tools | Seller-created discounts managed in Seller Center | Discounts drive conversion; competition may raise incentive to manipulate social proof | Greater focus on authenticity of endorsements and shopping claims |

| TikTok Stories viewer visibility | Stories can show who viewed them | Creates privacy demand and a market for risky third-party tools | Platform privacy settings changes and scams tied to “viewer” tools |

FAQ

Is offering “free TikTok likes” legal for a business to use in marketing?

It can create legal risk when it is used to deceive consumers or inflate indicators of influence tied to endorsements or sales, and regulators have signalled greater scrutiny of deceptive practices.

What is the safest way to buy TikTok coins?

TikTok describes purchasing Coins through in-app Balance settings and completing the transaction through the app store flow, with age limits for purchasing.

How do TikTok Shop promo codes work?

TikTok’s seller education materials describe creating promo codes in Seller Center with defined parameters such as validity period and discount rate constraints.

Can people see that I viewed their TikTok Story?

TikTok’s help pages indicate that Story viewing can be visible to the Story creator and explains how Stories are watched and viewed.

Conclusion

“Free TikTok likes” can look like a harmless growth hack, but in a platform economy now tied to shopping discounts, creator payouts and in-app spending, inflated engagement can carry real financial and compliance risk. As TikTok Shop expands and creators rely more on commerce-linked revenue, regulators and brands are paying closer attention to whether popularity signals are genuine and whether consumers are being misled. For readers, the key point is not that every viral post is suspicious, but that the value of trust in social metrics is rising and the cost of manipulation is rising with it.