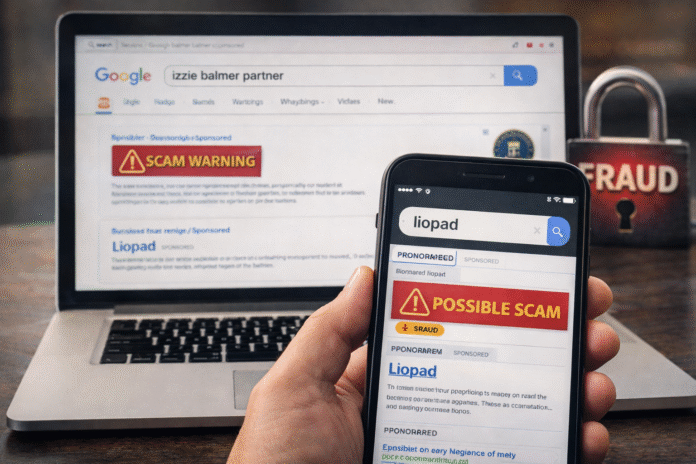

Typing a phrase like “izzie balmer partner” into a search bar may feel like harmless curiosity. So might looking up “liopad” after seeing the term in an app store, a social post, or a message from a colleague. But ad buyers, consumer advocates and fraud analysts say these everyday queries increasingly sit inside a fast-moving marketplace where attention is bought, sold, and sometimes exploited.

The financial significance is not in any single query. It is in the plumbing behind them: the auction-based advertising systems that price a click in real time, the affiliate networks that pay for conversions, and the copycat tactics that can turn search intent into a fraud opportunity. Regulators and law enforcement have repeatedly warned that many modern scams begin with simple digital prompts an ad, a message, a link—and then escalate into payment losses that are hard to recover. In the US, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center said reported losses across cyber and online crime exceeded $16 billion in 2024. The US Federal Trade Commission has also reported that investment scams are among the categories associated with some of the largest losses it tracks.

The keyword “izzie balmer partner” is a useful example because it is a high-intent phrase that can attract a wide audience quickly. Izzie Balmer is an English auctioneer and antiques TV presenter who has appeared on BBC daytime programmes including Antiques Road Trip and Bargain Hunt, according to her biography and industry profiles. Public interest in a presenter’s personal life can create predictable spikes in search traffic, and in digital advertising, predictable traffic often draws opportunistic content.

“Liopad” is a different type of case. The term can point to legitimate software products such as Li.PAD, a mobile mapping and GPS surveying app used in the energy and public lighting sector in Italy, according to its official materials and app listings. But ambiguity also creates room for lookalikes: pages that mimic legitimate brands, ads that redirect through multiple hops, or websites designed to harvest data. Fraud teams say that when users are unsure what a term refers to, they are more likely to click the first credible-looking result especially if it is labeled as sponsored.

The keyword economy behind everyday searches

Search advertising works because it captures intent at the moment it forms. Someone searching “izzie balmer partner” is signalling curiosity, and curiosity converts well for publishers running entertainment content and ad networks selling traffic. Someone searching “liopad” may be trying to find an app, a company website, a login portal, or documentation, and that intent can be monetised by legitimate marketers.

But the same mechanics can reward low-quality or deceptive behaviour. A common pattern in the ad ecosystem is “arbitrage,” where a publisher buys cheap clicks (or generates them via social posts), drives users to a page filled with ads, and profits on the difference between what it paid and what it earned. When done transparently, it is just a business model. When done aggressively, it can create a flood of thin pages designed to rank for high-intent keywords, with little value beyond capturing traffic.

The risks rise when keywords are connected directly or indirectly to money. Celebrity queries can be used as bait to lead users toward unrelated offers. Ambiguous software terms can be used to lure users into downloading the wrong app or entering credentials on a clone site. And if a user is redirected from a search result into a “high returns” pitch, the pathway can begin to resemble the investment-scam funnels regulators warn about, even if the initial query had nothing to do with investing.

That is why banks, payment companies, and platforms are watching the front end of the funnel more closely. The losses may show up later as disputes or fraud reports, but the first step is often a click.

For public figures, the problem also becomes reputational. Their names can be used in ads they did not approve, or on pages that imply endorsements. Izzie Balmer’s public profile built through television work and professional valuation roles makes her name recognisable enough to generate searches. The greater the recognition, the more valuable the keyword can be in the attention marketplace.

For businesses, “liopad” illustrates the brand-safety problem from the other direction. A legitimate product can still be harmed if search results are crowded by unofficial mirrors, affiliate pages, or misleading ads. Li.PAD’s own materials describe a specialised tool for field mapping and network census work, which suggests a user base that may include municipalities, contractors, and technical firms. Those users may be particularly sensitive to impersonation because access credentials and project data can be valuable.

Where the money is and why it matters for markets

For investors, the question is not whether one keyword is risky, but how the digital ad and security ecosystem responds. The keyword economy sits at the intersection of advertising budgets, platform moderation costs, and consumer trust factors that can influence earnings for ad-driven media, social platforms, ad-tech intermediaries, and cybersecurity vendors.

When scams surge, platforms often spend more on detection and enforcement. That can pressure margins, but it can also support demand for verification tools, fraud analytics, and identity services. The same dynamic can show up in payments and banking, where firms invest in monitoring and warnings to reduce push-payment fraud and to limit reimbursement exposure.

The flow of money can be hard to track because it crosses multiple systems. A user searches “izzie balmer partner,” clicks a sponsored result, lands on a page with more ads, then clicks again. Each step may pay someone: the ad platform, the publisher, the intermediary, and sometimes an affiliate. The user experience may feel like a maze, but each turn can be monetised.

That monetisation is why suspicious activity can persist even when it is widely recognised. If a deceptive page still generates “acceptable” engagement metrics time on site, click-through rates, low immediate complaint volumes it can continue earning. Regulators and consumer groups argue that this is part of the structural challenge: incentives are not always aligned with consumer protection.

The wider scam landscape reinforces the point. Law enforcement and regulators have stressed that online crime can scale quickly, and that it often crosses borders. The FBI has repeatedly urged reporting and awareness as a way to disrupt patterns, while consumer agencies have highlighted that investment-related scams can lead to large individual losses. Crypto-focused research firms have also described how online fraud models can be industrialised, with structured outreach and laundering pathways that evolve over time.

None of that means a search for “liopad” is inherently dangerous, or that “izzie balmer partner” is more than a celebrity curiosity. It means the systems that serve results and ads operate at scale, and scale makes them attractive to both legitimate marketers and criminals.

What to watch next

One area to watch is how platforms handle ambiguous or “multi-meaning” terms like liopad. When a keyword can refer to multiple things, ranking and ad placement become more important. If the official product is Li.PAD, but the user types “liopad,” the platform must decide what to prioritise. App-store listings and official product pages provide grounding, but search results can still be crowded by unofficial content.

A second area is how quickly platforms react to misuse of public names. As public figures build brands across television, social media and commerce, name-based searches become more valuable—and potentially more exploitable. For someone like Izzie Balmer, whose professional identity is documented through programme appearances and industry roles, there is a clear public interest component. The question is whether ad systems and social networks can reliably stop impersonation and misleading endorsements without suppressing legitimate commentary and journalism.

A third area is consumer behaviour. Fraud analysts often argue that “friction” is not always bad. Additional verification steps, clearer labels for sponsored results, and warnings before leaving a platform can reduce harm, even if they make experiences slower. In an environment where reported cybercrime losses are rising, the appetite for more safeguards may grow particularly among users who have experienced account takeovers, payment fraud or identity theft.

For businesses, the pragmatic response is usually less about any single term and more about resilience: stronger brand monitoring, clearer official channels, and faster reporting of impersonation. For consumers, the lesson is narrower: the first click matters, and ambiguous keywords can be an early warning sign that extra care is needed.

The broader story is that modern finance increasingly relies on digital distribution of content, of products, of payments and that distribution runs through systems built to maximise attention. “Izzie balmer partner” and “liopad” are simply two small windows into how that attention is priced, routed and sometimes abused.

Table: What “izzie balmer partner” and “liopad” reveal about keyword risk

| Keyword type | What the user may be trying to do | Typical monetisation | Main risk | What to watch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public-figure curiosity (“izzie balmer partner”) | Read background information or personal-life coverage | Sponsored results, publisher ads, affiliate traffic | Misleading endorsements, clickbait funnels, impersonation pages | Clear source signals, reputable outlets, transparent sponsorship |

| Ambiguous product term (“liopad”) | Find a legitimate app, login, or documentation | App installs, paid search ads, partner pages | Lookalike downloads, clone sites, credential harvesting | Official product pages, verified publishers, consistent branding |

FAQ

Q1: Is searching “izzie balmer partner” risky by itself?

Not necessarily. The risk depends on what links appear and where they lead. High-traffic celebrity queries can attract low-quality or misleading pages because they monetise well.

Q2: What is Li.PAD, and is it related to “liopad”?

Li.PAD is a mobile mapping/GPS surveying product described in official materials and app listings, particularly for network and public-lighting field surveys in Italy. “Liopad” can also be used more loosely online, which is why users may see mixed results.

Q3: Why do scammers care about search keywords?

Keywords capture intent. If a user is already looking for something, a convincing ad or page can redirect that intent toward a scam funnel, sometimes ending in payments or credential theft.

Q4: How does this connect to finance and markets?

The costs of fraud and enforcement can affect ad platforms, payment providers, and cybersecurity spending. Regulators and law enforcement have reported large and rising online-crime losses, underscoring why firms invest heavily in detection and prevention.

Conclusion

“izzie balmer partner” and “liopad” may look like harmless search queries, but they show how modern attention markets work: intent is valuable, ads compete for it, and bad actors can try to hijack it. As online fraud losses remain high and enforcement costs rise, platforms, banks, and advertisers are likely to face continued pressure to tighten verification and reduce deceptive traffic without breaking the convenience that keeps digital finance and commerce moving.